Shaping

Frequently Asked Questions

In sourdough baking, there are three shaping steps:

- Pre-shaping

- Bench Rest

- Final Shaping

1. Pre-shaping – Pre-shaping is the process of rough shaping your bulk fermented dough into a round to prepare it for final shaping. Pre-shaping the dough helps build additional height and create surface tension. For multi-loaf batches, it also creates equal size and weight rounds of dough for consistency in final shaping.

2. Bench Rest – The bench rest is not an actual shaping step but is an important part of the shaping process. It allows the dough to relax between pre-shaping and final shaping. The dough will be more extensible for final shaping after the bench rest.

2. Final Shaping – Final shaping takes the pre-shaped round and shapes it into a loaf. Final shaping typically also builds height, structure and surface tension. Typical shapes of sourdough loaves include boules and batards.

The “Caddy Clasp” is a final shaping technique popularized by Wayne Caddy. It is a quick, simplified method of shaping, that essentially squeezes the dough togehter rather than folding, rolling or stitching the dough.

In my experience, the method produces tall, symmetrical loaves with very nice shape, height and structure.

Here is a video demonstration. This is the “double clasp” method. https://www.instagram.com/reel/C4LVQq1Ngsu/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Pre-shaping is not required in three typical scenarios:

- You are making a single batch of dough. If there is no need to divide a large batch of dough, the dough coming out of bulk fermentation may already be sufficiently formed for final shaping. Especially if you do something like coil folding late in the bulk fermentation process.

- The dough has sufficient strength and structure coming out of bulk fermentation. For example, if you have built sufficient dough strength in bulk fermentation, some bakers go directly to the final shaping step.

- The dough is overproofing. If your dough is overproofing coming out of bulk fermentation, sometimes it is beneficial to proceed directly to final shaping and place the loaf in the refrigerator as quickly as possible to slow down the fermentation process. Or in some cases, with severely overproofing dough, it is beneficial to shape and bake the loaf as quickly as possible.

In pre-shaping, you want to think about building structure and building surface tension. You can build structure by gently stacking or folding the dough to create dough height. By gently tightening and rounding the dough, you build surface tension on the skin of the loaf. Be careful not to overtighten the dough. It is easy to create a weak spot on the top center of the skin if it is stretched too tightly. Also use minimal flour in this step to ensure your seams adhere in final shaping.

Your pre-shaping technique should consider the dough strength coming out of bulk fermentation. If your dough is very strong, you can do a looser pre-shaping. If your dough is loose, you should do stronger pre-shaping.

See the videos below for examples of different pre-shaping styles.

Here is an example from Maurizio Leo of The Perfect Loaf demonstrating how to shape a boule. See additional examples in the video section below.

Here is an example from Maurizio Leo of The Perfect Loaf demonstrating how to shape a batard. This is a simple shaping without the “stitching” step you will see in other videos. See additional examples in the video section below.

The most common loaf shapes —boules, baguettes, and batards come from the French names for these loaf shapes. In French, “batard” means “bastard” which is a peculiar name for a loaf of bread. How did it get this name?

In France, the shape and weight of bread loaves are strictly regulated. The two “regulated” shapes initially included boules and baguettes. When batards were invented, they were neither a boule nor a baguette, but something in between. Hence, they were referred to as a “bastard” loaf, or an un-natural cross between a boule and a baguette.

In French, the use of the term “bastard” is more similar to a “cross-breed,” or “mongrel” as opposed to “illegitimate offspring” which may be the more common usage of the term in other countries.

The batard is not a “pure-bred” (or is that “pure bread”) loaf in French. It is a mongrel, or a cross-breed of two pure-bred styles.

This video from King Arthur Baking demonstrates pre-shaping and final shaping of a sourdough baguette. Note: this method does a bit more de-gassing of the dough than some others.

Shaping baskets are required because the dough would flatten into a pancake without support. Because sourdough is a high hydration dough, it does not hold its shape in final proofing without some support.

No. You can use any kitchen vessel to hold the dough shape. For boules, I use various sized salad bowls lined with a flour sack cloth (i.e., a thin linen kitchen towel). Some bakers use colanders. I dust the cloth with a 50/50 mix of bread flour and white rice flour to prevent it from sticking to the cloth.

For batards, I use small loaf pans. Loaf pans will produce a somewhat more rectangular shape than traditional oval bannetons, but you can gently tuck and round the corners of the loaf before scoring and baking.

Bannetons, typically made from natural cane or rattan, help wick moisture away from the surface of the loaf. This is a benefit of using bannetons. Also look into a new type of bannetons made from natural wood pulp. Many bakers are switching from the rattan bannetons to natural wood pulp.

Dust your bannetons with a 50/50 mix of bread flour and white rice flour.

Some bakers use 100% rice flour. Gluten-free flours help keep the loaves from sticking to the bannetons or the liners.

Some bannetons come with a linen liner. It is bakers’ preference if you choose to use the liners or not. A few recommendations.

- Most bakers wash the liners before using them.

- If you wash the liners, use an unscented detergent.

- You do not need to use the liners. You can put your dough directly in the wooden banneton.

- If you use the liners, you will not see the lined patterns on the loaf.

- You should dust the liners with a gluten-free flour. I use a 50/50 mix of rice flour and bread flour.

No. You want to use as little flour as possible when shaping your loaves. Flour creates weak seams in the dough. It will not stick to itself. And these seams become weak points which reveal themselves as irregularities in the loaf when baked. Try to wet your hands with water and use as little flour as possible. This takes practice. Stick with it.

No! When working with traditional commercial yeasted dough many recipes say to “punch down” the dough before shaping. This is because commercial yeast is so unnaturally powerful that it can overinflate a loaf after shaping. Sourdough, on the other hand, does not have the rising power of commercial yeast so you want to handle it as gently as possible to prevent loss of the carbon dioxide in the loaf.

You will see in the videos below many examples of expert dough handling. It is a combination of very light handing with a few moments of strategic stretching and tighter shaping. Watching how other bakers handle the dough is the best way to learn these techniques.

I have done a number of experiments on this topic in my “In Search of Open Crumb” series. Two of the videos are posted below. In these videos I bake four loaves with different types of pre-shaping, and four loaves with different types of final shaping. The experiments were fascinating, and the results are surprising:

- Final shaping had a small impact on open crumb, but not as much as expected.

- Pre-shaping introduced a lot of variability into the crumb.

The most fascinating results came in Part 3 of this series, “The Impact of Bulk Fermentation on Open Crumb.” Those results were mind-blowing. 80% of the final crumb of a sourdough loaf is established in bulk fermentation. The other 20% is attributed to all other variables including pre-shaping and final shaping.

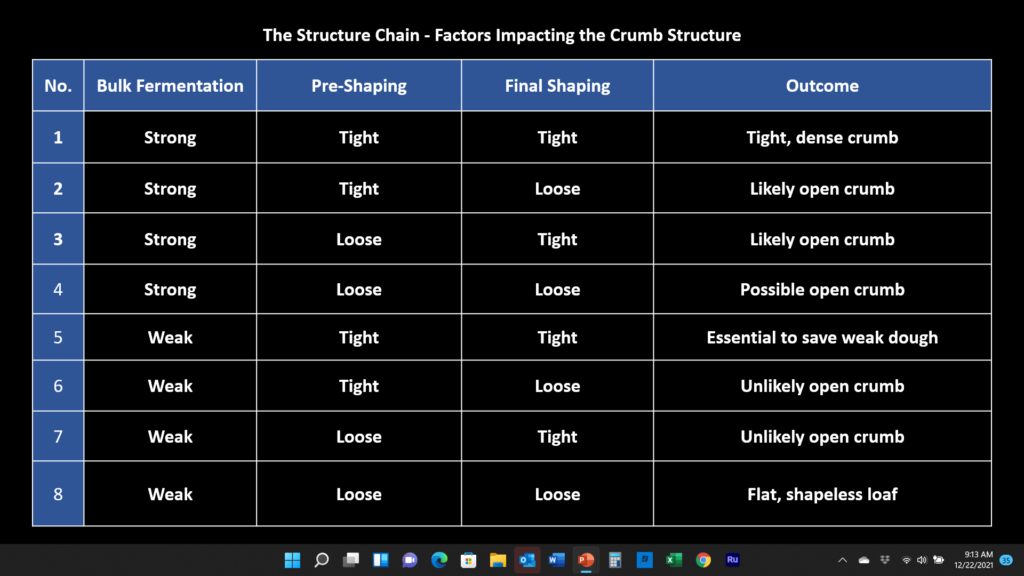

The Structure Chain is a concept I describe in my videos which analyzes the cumulative effects of 1) dough strength coming out of bulk fermentation, 2) pre-shaping techniques, and 3) final shaping techniques.

By assessing the condition of the dough in the preceding step(s), the baker should adjust their approach in the remaining steps. For example, if you have very strong dough coming out of bulk fermentation, you can skip pre-shaping and do a moderate final shaping. If you have very weak or loose dough coming out of bulk fermentation, then you need to do tighter pre-shaping and final shaping.

The following chart shows the 8 combinations of these variables and the likely outcome from each combination.

The Structure Chain is discussed in this video clip:

This is one of the (few) areas that you really can only learn through experience. Most recipes do not call for a countertop rise after shaping before going into the fridge. But there are a few cases where you would want to do it:

1) Your bulk fermentation did not achieve the target % rise before shaping, or

2) The dough still feels stiff or not fully proofed when shaping.

In either of these cases, it may make sense to let the dough sit on the countertop for 30-90 minutes (maximum) before going into the fridge.

Some bakers routinely allow their dough about 30 minutes on the countertop after shaping to allow the dough to open up a little bit after the de-gassing from shaping, before going into the fridge. But if your dough is really far along (proofing-wise), this step is not advisable. And some bakers build this time into their bulk fermentation cutoff (knowingly or unknowingly). If they always do a 30-minute bench rest before the cold retard, they may actually cut bulk fermentation a little short knowing that this step is ahead.

If you see large air bubbles on the surface if your dough when shaping, you should pierce and deflate those bubbles.

I use the tip of my probe thermometer to pop the surface bubbles, then gently pat them down with my fingertip.

videos

Pre-shaping

This is my method for “strong pre-shaping.” I think of this as an “upside-down coil fold.”

I use this method with proofy dough, or in cases where I have not done any stretch and folds in bulk fermentation, and need to build maximum height and structure with the pre-shaping.

The “Caddy Clasp” Method

This is an Instagram post by Wayne Caddy, demonstating his popular final shaping technique, the “Caddy Clasp.”

I’ve used this method with good results.

How to Shape a Boule: Chad Robertson, Tartine Bread

Chad Robertson shows his pre-shaping and final shaping techniques for a boule. His pre-shaping is very light but note the incredible dough strength as he cuts the dough away. The height and edge is amazing.

Also, in his final shaping he does the Tartine fold with an added “stitching” step. That step is not in the Tartine Bread book but is a common technique among sourdough bakers.

How to Shape a Boule, The Perfect Loaf

Maurizio Leo demonstrates final shaping of a boule. This is fairly light final shaping with no stitching.

How to Shape a Batard, The Perfect Loaf

Maurizio Leo demonstrates final shaping of a batard. This is the technique I use for shaping batards in most of my videos.

Pre and Final Shaping of Boules and Batards, Simple Sourdough

Peter Jesperson of Simple Sourdough demonstrates dividing, scaling, pre-shaping and various final shaping techniques in this video.

Note how he does a partial coil fold when taking the dough from the scale to the bench for pre-shaping. His pre-shaping is quite light, but this partial coil fold is an important part of that step.

The Impact of Final Shaping on Open Crumb

In this video, I perform a four-loaf experiment on the impact of final shaping on open crumb. The results are surprising.

The Impact of Pre-Shaping on Open Crumb

In this video, I perform a four-loaf experiment on the impact of preshaping on open crumb. The results are fascinating.

At the end of this video, I discuss “The Structure Chain” in detail. It is the interplay of bulk fermentation, pre-shaping and final shaping — and it is one of my most important findings.

Additional resources

Coming soon…